Last week, myself and my colleague had the amazing opportunity to assist two research technicians from North Carolina State University with Neuse River waterdog surveys in the Eno and Flat Rivers. Spoiler alert: we found one in the Flat River, but none in the Eno. Nonetheless, I’d like to tell you about our experience!

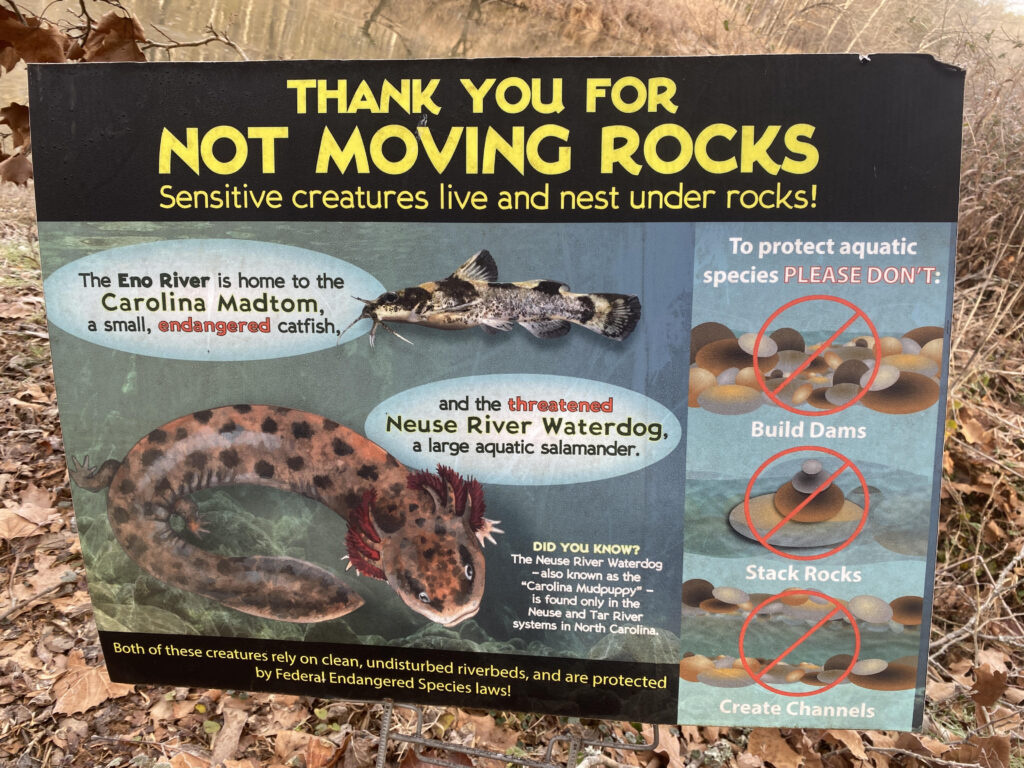

First, I’ll provide a little background information. The Neuse River waterdog (Necturus lewisi) is an aquatic salamander species endemic to the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River Basins. This means they are found nowhere else in the world! Neuse River waterdogs are paedomorphic, retaining their juvenile characteristics such as gills and a flattened tail for their entire life, never venturing onto land as many other salamander species do in their adult form. These salamanders are ambush predators and spend a great deal of their lives hiding under rocks and other debris before pouncing on prey such as small fish, tadpoles, and macroinvertebrates.

Neuse River waterdogs rely on cold, clean water in order to survive. In recent decades, their populations have decreased dramatically, as much as 43% in Piedmont watersheds. In response to these significant and alarming population declines, these salamanders were listed federally as Threatened in 2021 and as a result now have a Recovery Outline with various important protections.

With all that being said, it is important to note that there is still a lot to learn about Neuse River waterdogs, and there are some substantial unknowns when it comes to their life cycle, reproduction, habitat requirements, conservation needs, and so on. Fortunately, NCSU PhD candidate Eric Teitsworth and his dedicated team of technicians and volunteers are looking to change that and have picked up where waterdog research projects from the 1980s and 2010s left off. With funding from the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Eric has been able to set up survey sites at many different locations throughout the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River Basins, and the Eno is one of them. The idea is to gather as much data as possible about Neuse River waterdogs, their population levels, and then use that information to inform future conservation efforts.

Neuse River waterdogs are cold-adapted and are most active during the colder months. Their mating season begins in the late fall and females typically lay eggs in the early spring. Because this is the most active time of year for these salamanders, it is also when sampling surveys take place. These surveys involve the use of minnow traps, which contain a small bottle of bait inside. (The salamanders cannot actually get to the bait to consume it but are simply attracted to the smell). There is a contraption within the trap that allows waterdogs (and sometimes other critters) to enter but not exit. The traps are checked every single day to ensure that no animal is left for very long inside.

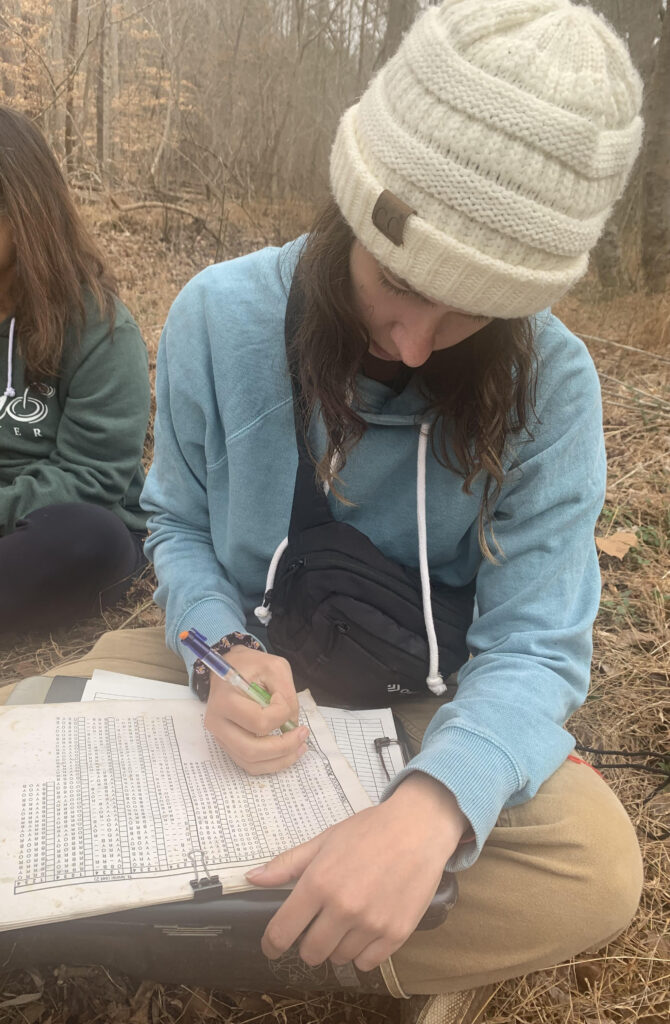

On the morning of our volunteering adventure, we met Eric’s two primary technicians, Caitlyn Connell and Kylie Hackett, at the Eno River State Park Fews Ford Access. We all had on either rubber boots or waterproof shoes and ample clothing for the chilly day. And so our adventure began! At each of the six sites we visited (five in the Eno and one in the Flat), there were ten minnow traps placed at specific intervals throughout the site. Each trap was attached to a sturdy string which allows them to be easily removed from the river in order to check their contents. While we helped to check traps, one of the technicians used water quality measuring devices to take certain measurements such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and conductivity at three different points within each sampling location.

Although a handful of Neuse River waterdogs have been caught in the Eno in recent years as part of Eric’s project, more often than not, the Eno comes up empty. Unfortunately, this was the case on the day that we volunteered with surveys, and the Eno minnow traps captured only some redbreast sunfish, a white shiner, and a crayfish. The presence of these organisms were recorded before they were promptly released back into the river.

Our luck changed at the Flat River sampling location where we were elated to discover a single medium-sized female Neuse River waterdog! When an individual is captured, a few things happen. First, the location and other relevant details are recorded. Then, their measurements (e.g., mass, snout-to-vent length) are taken and if possible, their sex is determined. Finally, they are tagged with a unique color code that allows for their easy identification if they are recaptured at any point in the study.

Being a part of this process and getting to see (and even briefly hold!) a waterdog in real life was incredibly exciting, inspiring, and thought-provoking – even if we didn’t find them in the Eno River itself.

But why is that? The Eno should be a perfect place for waterdogs to live and breed. There are plenty of locations along the Eno that have the rocky substrates, leaf litter, and low to medium flow that these salamanders need in order to survive. At other sampling locations in Eric’s project, waterdogs are caught regularly, sometimes multiple in each trap. But not in the Eno. So where are they? Why have there been so few caught in recent years?

Eric believes that the answers lie in increased development, urbanization, and subsequent stormwater runoff along the Eno. Unfortunately, as riparian buffers are lost and surrounding areas are developed, this means that more pollutants are entering our local freshwater systems. Amphibians are particularly susceptible to such pollutants since they have permeable skin that takes in toxins from the water around them. It is undeniable that Durham is expanding and that human action will continue to impact our beautiful river, and human-caused climate change may be negatively impacting species like the Neuse River waterdog that rely on cooler temperatures for their life cycles and survival.

But human action can also help counteract these factors, and that’s what the Eno River Association and land trusts like us are trying to do by protecting land along the river, advocating for responsible development and stormwater systems in critical areas, restoring riparian buffers, replanting natives, building climate-resilient communities, and educating the community about the importance of this work for future generations!

In order to help something, you must first understand it, which is exactly what Eric and his team are trying to do. Studies like this one are critical in helping us to understand how our actions impact our waterways and the incredibly special organisms that call them home. Although the fate of Neuse River waterdogs in the Eno is looking pretty grim, not all hope is lost! Five individual waterdogs have been found in the Eno over the course of Eric’s project, so they are still present, albeit in small numbers. As we continue our work to protect the Eno, there is the potential for reintroduction of the Neuse River waterdog into the Eno at certain locations.

There are also things that you can do to protect this species. First and foremost, don’t move rocks! Moving a rock or a shell moves key parts of these organisms’ habitats. Second, do your best to reduce the amount of waste you are producing and properly dispose of any fertilizers, pesticides, or other chemicals. Finally, support local organizations fighting to protect freshwater resources and speak out against problematic developments. Although humans tend to wreak a lot of havoc in the natural world, we also have the unique ability to make intentional, meaningful change, and this is best done together, as a community. Join us in fighting for the Neuse River waterdog and for the Eno!

Written by Audrey Vaughn, AmeriCorps Environmental Educator at Eno River Association