ENO Journal

VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1

1989

by Jean Bradley Anderson

Special thanks to:

William Few

Lyne Few

Kendrick Few

Randolph Few

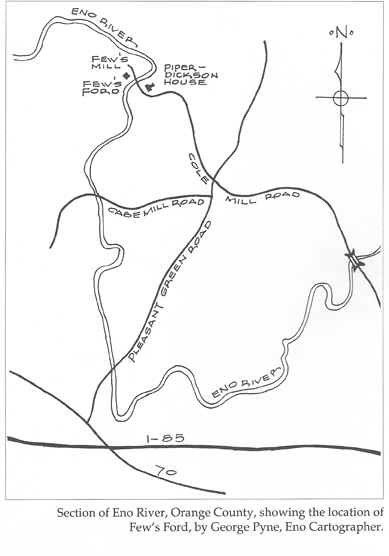

The banks and hinterlands of a stretch of the Eno River that runs directly south near the eastern boundary of Orange county, North Carolina, once comprised a distinct community, whose history was played out over one hundred and fifty years. At its beginning in the 1750s, the scene was the wilderness the first settlers found. As population and activity grew, it subtly changed over the years to increasingly cleared fields and ordered landscape. After the Civil War, the population and activity began to wane, and the forest slowly returned with the quiet and isolation it now enjoys. This history focuses on two mills that stood at a ford and their owners – the nucleus of the neighborhood.

The story begins in 1758 when a farmer in Baltimore County, Maryland, having lost several successive crops by killing frosts, decided to come south in search of a milder climate and richer soil. He persuaded several of his neighbors to come too, and the land they found to settle on was precisely this stretch of Eno River. The colonial government’s establishment in the 1750s of Orange County and its seat at Hillsborough was a response to the flood of immigrants into the backcountry from the mid Atlantic colonies. The farmer from Maryland, William Few, Sr., was just one of thousands arriving at that time. 1

The land Few bought in 1758, lying on both sides of the river, was 640 acres that had been part of an approximately 9,000-acre grant from Lord Granville to Governor Gabriel Johnston. 2 In 1759 William Few, his brother James, and James’s step-son, John Wood, built saw and grist mills on two acres obtained from William Cox at a fording place not far upstream from Few’s new homestead.3 A mill already existed on the Eno in Hillsborough seven miles upstream, and another slightly farther away downstream, so that the Few mill could count on a wide radius of potential custom. Among those already settled along that stretch of river, besides the Fews and Wood, was Barnaby Cabe – probably one of the neighbors who moved south with Few. He registered his cattle mark al the courthouse in 1758 and in 1759 bought well over half of Few’s 640-acre purchase: the part on the east side of the river.4 Also settled along the river were James Denny, in the Buck Quarter Creek area, John Watson (soon to sell out to John Piper), Edward Stone, and John Flintom.5

In 1763, possibly attracted by the amenities and potential for business that Hillsborough offered, William Few bought a tract of land east of Hillsborough (where Ayr Mount plantation house stands today) and took advantage of its location on the Indian Trading Path to “keep tavern”’ at his house. The following year he sold his interest in the mill. 6 The records do not disclose how much longer it continued to operate. lt has left few visible remains: downstream from the ford on the west side of the river is a large, rounded-out hole where the waterwheel turned. Upstream, a natural rocky outcrop in the riverbed provided a strong footing for the dam. When the water level is down, it is still possible to climb dryshod from one bank to the other.

By 1770 William Few was in a financial bind. He had gone bond for the Regulator leader Herman Husband and signed promissory notes for friends who had defaulted on their loans. Like other Quakers in the Hillsborough area, he decided to move to Georgia and start afresh. 7 The move was hastened by the dangerous turn the Regulator movement took that year. Unrest that had been brewing over five years broke out in violence: the Regulators took over the Superior Court session in September, destroyed the house and possessions of Edmund Fanning, threatened other members of the courthouse ring, and generally behaved badly. Among the leaders of this unruly mob was Captain James Few, William Few’s second son.8

The Regulators have been lauded by some historians as forerunners of the Revolutionary patriots and denounced by others as rabble-rousers. However viewed, they were citizens angered by the abuses of power and greed of local officials, who exploited their offices for private gain by charging exorbitantly for their regular services. When attempts to correct the situation by legitimate means failed, the Regulators in frustration resorted to civil disobedience and, ultimately, force. Force begets force, and in May 1771 Governor Tryon’s troops took only a few hours to subdue a host of Regulators at the place known now as the Alamance Battleground.

The day after the battle, James Few was summarily hanged. Fanciful stories about him have been offered to explain his participation in the movement. One painted him as enraged by Edmund Fanning’s seduction of his intended bride; another labeled him a fanatic with prophetic visions of himself as a deliverer of the people from tyranny. Unquestionably, high emotion informed both factions. Governor Tyron explained the death sentence as appeasement to an angry soldiery, though he was reluctant to order it; but even after repeated urgings, Few refused to take the oath of allegiance required of Regulators as the condition for their pardon, and Governor Tyron had no recourse but to hang him as a traitor. it is also true that some time later, while the army was encamped outside Hillsborough, Tyron ordered the army cattle and horses turned loose into Few’s plantation and allowed to triangle the crops as fit recompense for his contributions to the civil disorder.9

After his death, James Few’s widow and three-month-old twins remained in North Carolina, but other members of the family, over the course of the next few years, moved to Georgia. When Sally Wood Few, James’ s widow, remarried in 1781, James’ s brother Benjamin fetched the twins from North Carolina to rear in his own home. One hundred and thirty years later, by a turn of fortune’s wheel, William Preston Few, a great grandson of James Few through both his father and mother, came back to the area of his ancestor’ s defeat as a professor at Trinity College in Durham.10 His efforts, however, were crowned with success: he persuaded James B. Duke to endow the little college and transform it into a great university, and Few became the first president of Duke University.

His son, another William Few, bought land in there of Few’s Ford and came to know it well. History, like time, is circular.

A longer history with the recurrent theme of dissent lies back of the Few family. William Few, Sr., was a grandson of Richard Few of Market Lavington, a Wiltshire village on the edge of Salisbury Plain. Domesday Book recorded the village in 1085-86, and Lavington obtained a charter for a market in 1254. By then one of its three mills was a fulling mill, evidence that Market Lavington participated in England’s thriving woolen industry. Salisbury Plain provided pasturage for thousands of sheep. By 1377 Market Lavington was a prosperous place with 252 taxables, and by 1620 the village economy supported eight inns and alehouses. Small home industries like weaving, tailoring, and shoemaking grew profitable. Richard Few, a cobbler, probably did a good business. 11

But Richard Few was a Quaker. The Society of Friends had a firm hold on that area of Wiltshire by the mid-seventeenth century. Market Lavington had twenty-four dissenters in 1674, probably all Quakers. That year a Quarterly Meeting of the Society was held in Devizes, five miles from Lavington, at which Richard Few was a delegate from Lavington Meeting. Though England was still persecuting and punishing non-conformists, their number continued to grow.12 Richard Few, however, was quick to take advantage of an alternative to remaining in England and enduring the economic and social disabilities of dissent. Like his grandson one hundred years later, he chose to move. In 1680 or 1681 he bought 500 acres of land in Pennsylvania, where William Penn was founding a colony for Quakers and others who wished to join him.13 In late 1680 or early 1681, Richard Few, his wife Julian, and a son Isaac sailed to the New World, and by September 1682 Richard Few was already involved in the civic affairs of Chester County, where his name appears on a court jury. Isaac Few, a weaver by training, eventually became the father of William Few, Sr., the North Carolina pioneer.14

As a young man, William Few, Sr., moved over the border from Pennsylvania into Maryland and there married a Catholic, for which act he was read out of meeting.15 Possibly the unpleasantness to ostracism from his fellow Quakers was additional cause of his moving to Carolina. Never afraid to disagree, the Fews nevertheless prospered. After their move to Georgia, William Few, jr., the older brother of the hanged James, had a distinguished career in the Revolutionary period as a soldier, a member of the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, a signer of the Constitution, and a United States senator.16

Phase two of this history concerns the second mill built at Few’s Ford. Samuel Scarlett, who had acquired much of the land around the ford, in

1811 sold to James Strayhorn and William McMillen seven acres on which to construct a tilt hammermill capable of heavy forge work.17 This mill was built just upstream from the ford, again on the west bank, and made use of the old dam and headrace. It continued to operate intermittently under various owners almost one hundred years.

In 1815, McMillen reorganized his partnership to include Michael Graham and a young blacksmith, John Farrar, who bought half interest in the tilt hammer shop, including the land, tools, and improvements. Farrar agreed to manage the shop for $180 a year plus $60 for board, lodging, and washing. The agreement also specified that Farer could reserve three months of the year in which to improve himself in writing and the like, in other words, for schooling. About two years later, the partnership was again reconstituted with Samuel S. Claytor replacing McMillen, the new firm to be called John Farrar and Company. At the same time, Claytor and Graham agreed to hire a wagon-maker for whom they would build a special shop. Farrar contracted to put the metal rims on the wagon wheels for S40 per wagon, if they supplied the iron.18

In 1818 Claytor bought out both his partners, Farrar and Graham, and ran the establishment alone until 1827 when, having defaulted on his mortgage, he was forced to give Dr. James Webb of Hillsborough half interest in the business. Clayton had more than one iron in the fire; he owned and operated carding machines at a number of mills on the river. An advertisement for the mill at Few’s Ford, then called Eno Mills, revealed it as an industrial complex manufacturing flaxseed oil, hoes, plows, wagons, and carryalls. When Claytor’s financial health did not improve, he relinquished his own half-ownership to Webb to pay his debt.19

In 1831 William Piper, whose father owned close to 600 acres on the east bank of the river, including the land opposite the mill and the log portion of the now restored Piper-Dickson House, took a leaden the mill and tried to build up the business. He advertised a blacksmith shop with three first rate smiths, a grist mill, oil mill, saw mill, wheat threshing machine, and wool carding machine. 20

Like all the Pipers for three generations, William had been educated at the Piper-Cabe schoolhouse, which last stood on a knoll near the ford. The first mention of the school is found in a land entry to 1778 in which William Cabe, Barnaby?s son, entered a claim for 18O acres of land “including the schoolhouse”. 21 The Cabes had probably established the school soon after their arrival in 1758, for as Presbyterians they were dedicated to educating their children. lt may, in fact, have been this school which William Few described in his autobiography. In 1760 a schoolteacher came into the neighborhood, he related, and was engaged by the families to teach the children for a session. The happy memories of that year remained with William Few, Jr,, till the end of his life. William Cabe’s marriage to Jamima Piper brought the Pipers, whose land adjoined the Cabes’, into the family and the proprietorship of the schoolhouse John Piper, Jr., Jamiina’s brother, left numerous schoolbooks as part of his estate. His son William, as his later career showed, was better suited to school teaching than mill-management. William Piper’s mill operation failed in l832.22

Fortunately for the mill, some time after 1835 Allen Brown, a skilled mechanic, became the owner of Eno Mills. He added a cotton gin to the other services the mill offered.23 When he established the Eagle Foundry upstream at the old Neal Mill thirteen years later, he apparently sold half interest in the tilt hammer mill to Alexander Dickson. 24 Dickson was a member of the family whose home place outside Hillsborough later won fame as the site of general Wade Hampton’s headquarters in the closing days of the Civil War. There, too, General Joseph Johnston stayed during his negotiations with General Sherman at the Bennett Place. Dickson eventually became sole owner of the mill complex, and under his owner ship it reached its apogee as Eno Mountain Mills.25

An advertisement under his name is worth quoting

l am engaged in Blacksmithing, Manufacturing Carding Machines, Wheat-fans, Wagons, Ploughs. Also on hand Flour, Wheat Bran, Corn Meal, Wool rolls and Shingles together with a small stock of foods, such as are generally found in a Country Store; all of which will be sold to suit the times for cash; or W/heat, Corn, Flaxseed, Feathers, Bees-wax, Tallow, and Shingles will be taken as cash at market prices.26

By mid-century Orange County had experienced much population growth; no one mill or community promised more than another. In 1852

a group of citizens living north of the Eno River, in a petition to the county court, voiced a concern that lack of bridges over the Eno handicapped them in transporting their produce “to the great southeastern thoroughfare by Wm. N. Pratt’s store into the Southeastern and Eastern markets.”27 They cited the fact that no bridge existed in the stretch between Hillsborough and Cameron?s lower mill (the Red Mill), a distance of eighteen miles. Because of frequent high water, which made fording the river impossible, they were forced to go round by one of the two bridges. They suggested the Guess mill crossing as a convenient location for a bridge. In 1853 another group petitioned for a bridge at Dickson’s mills. The court looked favorably on this second site and ordered bids to be let for a bridge, but apparently the justices soon afterwards rescinded their ord er. The bridge was built instead at the Roxboro Road crossing, the site of West Point or Sims mill.28

The state railroad survey of 1850, which routed the railroad along the ridge through the middle of the county by Pratt’s store, closely paralleling the Hillsborough Road, and the court’s decision to construct the bridge at West Point Mill were decisive factors in the history of Eno Mountain Mills. Because of them, traffic and population patterns evolved in such a way as to leave that stretch of river a backwater. If the bridge had been built there, a rather different conclusion to this story would follow.

The 1850s were a prosperous decade but politically ominous as public opinion polarized about the issue of states rights. When valiant efforts by North Carolinians to prevent a dissolution of the Union failed the usual wartime problems for the general populace followed: shortages of all kinds, inflation, and widespread privation. In 1863 Dickson sold his mills, probably unable to carry on under the economic stringencies of the of the waryears. The complex then passed through a succession of owners with many lapses in its operation and declines in its services, until the severe flooding in August 1908 damaged it irreparably.29

An historical footnote concludes the story. George Piper, a brother of William, claimed that at Eno Mills cottonseed oil was first processed under pressure. The Moravians had earlier boiled the seed in water and drained the oil from the top of the water as it was released. In 1828 when Claytor and Webb owned the tilt hammer mill, George Piper was an apprentice to the mechanic, James W. Brown. They were manufacturing horse-powered corn mills, and they kept one set up as a model for prospective buyers. One day a customer came to see it operate when George was alone in the shop. Because there was no corn on hand, substituted cottonseed, and the mill hulled the kernels quite acceptably.

Later he showed Brown what he had done, and together they adjusted the hulledmill to perfect the process. When they tried pulverizing the hulled cottonseed kernels in the flaxseed press to extract the oil, however they found the seeds contained too much oil for this press to function properly.

They then made a good many adjustments to the press, any succeeded in collecting several hundred gallons of cottonseed oil. Nevertheless they abandoned their efforts, conceding that their machine was not suited to the purpose. Piper claimed that if they had persevered in refining the process, they might have made a valuable invention. “My discovery”, George Piper wrote in 1890, “was the first on record of pressing the oil out of the seed” 30

Today we see this stretch of river not unlike the way it must have looked to William Few in 1758: tall trees, a free-flowing river, the land almost empty of inhabitants. The populous and busy farmsteads of the many intervening year have vanished, an traces of the mills lie hidden in the earth. That they were once vital adjuncts to agriculture and social centers for the widely scattered farm there can he no doubt. But political decisions about road~ and bridges, population drift from the farm to the city, technological improvements that freed milling from riverbanks, and the unleashed power of the river in spate doomed the watermills. With them went the community and nature reclaimed her own: another instance of history come full circle.

——————————————————————————–

Footnotes:

1 William Few, jr., “Autobiography of Col William Few of Georgia,” Magazine of American History 7 (1881). 343—358

2 Orange County Court Minutes, March 1759, North Carolina Archives. (The minutes record the date as 15 ]an. 1758.) Hugh Conway Browning, “Valley of the Eno: Some of Its Lands, Some of It’s People, Some of lts Mills,’ (1973), 26 (typescript in the possession of the author.

3 Orange County Deed Book 3: 373.

4 Orange County Court Minutes, March 1759; Browning, “Information Relating to the Cabe (McCabe) Family of Orange County, North Carolina,” 1 (typescript in possession of the author).

5 A.B. Markham, “Land Grants to Early Settlers in Old Orange County, North Carolina,” 1973.

6 Orange County Deed Book 3: 215 (Thomas Wiley to Few) and 373 (Few to Milner); Orange County Minutes, Aug. 1763, North Carolina Archives.

7 Autobiography of Col. William Few,” 345; Florence Knight Fruth, Some Descendants of Richard Few of Chester County Pennsylvania and Allied Lines (Beaver Falls, Pa., 1977) 59.

8 Fruth, Some Descendants of Richard Few, 57-60

9 William L. Saunders, ed., The Colonial Records of North Carolina (Raleigh, 1886-1890) 19 845, 852; Frank Nash, “James Few,” Biographical History of North Carolina (Greensboro, N.C , l905) 1:90-92, 181 William Henry Foot, Sketches of North Carolina, Historical and Biographical (New York, 46), 61

10 Fruth, Some Descendants of Richard Few, 63, 71-74

11 lbid, 6-7; Victoria County History, The History of Wiltshire (Oxford, 1948), 82, 83, 94, 98, 100

12 Ibid., 104 “The Quakers of Wiltshire/’ 23, a pamphlet to accompany an exhibit at Devizes Museum. l am grateful to John Patrick Manley of Market Lavington for this source.

13 Fruth, Some Descendants of Richard Few, 7-9

14 Ibid., 8-9, 11-15.

15 Ibid., 21.

16 Ibid., 21.

17 Browning, “Valley of the Eno”, 28

18 Orange County Records, North Carolina Archives, Miscellaneous Records, Mills, 7 Mar. 1815, 16, 17 Dec. 1815

19 Browning, “Valley of the Eno,” 28,: Hillsborough Recorder, 8 June 1825, 6 Aug. 1828

20 Jean B. Anderson, “The Federal Direct tax of 11816 As Assessed in Orange County, N.C.,” North Carolina Genealogical Journal 5 (Feb 1979); 21 Hillsborough Recorder , 25 July 1831

21 Interview with Mrs. Vesta Langley; Land Entry Book, 1778-1779, North Carolina Archives.

22 “Autobiography of Col William Few, lr,,” 344; Orange County Records, North Carolina Archives, Estates: John Piper, Jr.; Henry Thomas Shanks , The Papers of Willie P. Mangum (Raleigh, 1950-1955)4; 308, 403-404 (Piper taught Mangum’s son, William Preston Mangum.) Hillsborough

Recorder, 10 Ocl1832

23 Browning, “Valley of the Eno,” 29; Hillsborough Recorder, 19 Sept 1839

24 Browning, ibid , 29-30; Hillsborough Recorder, 7 Feb. 1852

25 Browning, “Valley of the Eno,” 30, Hillsborough Recorder, 24 Oct 1849; interview with Helen Dickson McKee, 30 Sept 1985

26 Hillsborough Recorder, 24 Oct 1849

27 Orange County Records, North Carolina Archives, Miscellaneous Records, Roads and Bridge.

28 Ibid., Hillsborough Recorder, 30 Mar. 1853, 28 Mar. 1855.

29 Browning, “Valley of the Eno,” 30-31.

30 Cameron Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, H.B. Battle to Paul Cameron, 1 Dec. 1890, enclosing a letter from George Piper to the North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station, 25 Nov. 1890